By Livingstone Nyando

Elections and security in Kenya just like in other emerging democracies are aptly getting increasing prominence. It is a known fact that the Kenya Police has served as the state’s primary organ of oppression and principal human rights violators operating in a culture of low accountability over the years. It is well documented that the police have often been charged with corruption and misuse of the service. Time immemorial, the Kenya Police has been linked with the protection of a small political and economic elite at the expense of the protection of all citizens’ rights: this contributed to the public’s image of the police as hostile, abusive, corrupt and ineffective. The aftermath of the 2007 elections was the turning point of the national police reform agenda.

The Commission of Inquiry into Post-Election Violence (CIPEV) implicated the police in acts of violence, torture and killings during the Post-Election Violence. The CIPEV and the UN special rapporteur report on extrajudicial killings both recommended extensive reforms of the police system. In response to these recommendations, the government set up the National Taskforce on Police Reforms in 2009 headed by Retired Judge Philip Ransley. The task force came up with over 200 recommendations, the key of which required police retraining.

The recommendations of the Commission became the basis for the process of police reforms in the country. In implementing the recommendations of the Commission, the National Accord recognized police reforms as one of the items under these Reforms Package.

The National Police Service is provided for in articles 238, 239, 243, 244, and 247 of the Constitution and operationalized with the enactment of the National Police Service Act 2011. One of the provisions of the Act was the merger of the Kenya Police Force and Administration Police to form the National Police Service and the creation of the Office of the Inspector General with two deputies.

Public protests that seek to challenge governments of the day and to question the legitimacy of those governments present particular challenges given the traditional attitudes and understandings by the police of their role and mission as enforcers and guarantors of the status quo through the maintenance of social order. Protests are avenues for people to be heard by the government and though intended to be peaceful, in many cases when the police are called in, lives are lost and property destroyed.

In their report on Rethinking Policing of Protests and Gatherings In Kenya, Dr Mutuma Ruteere and Patrick Mutahi state that ‘the management of public order in fledgling democracies presents unending dilemmas, questions and challenges that speak to the theory as well as the practice of policing. The report goes ahead to state that these challenges, tensions and dilemmas are particularly amplified in fledgling democracies struggling to establish and solidify a culture and practice of adherence to the rule of law while at the same time building confident, effective and accountable police services. Keeping public order is one of the traditional missions of police services.

Unlike the previous elections where the presidential election was marred by serious human rights violations, including unlawful killings and beatings by police, this year’s election was relatively peaceful. This can be attributed to several interventions by both state and non-state actors who burnt the midnight oil by filling the gap between the promise and the reality for policing and police conduct in public order management during the electioneering period.

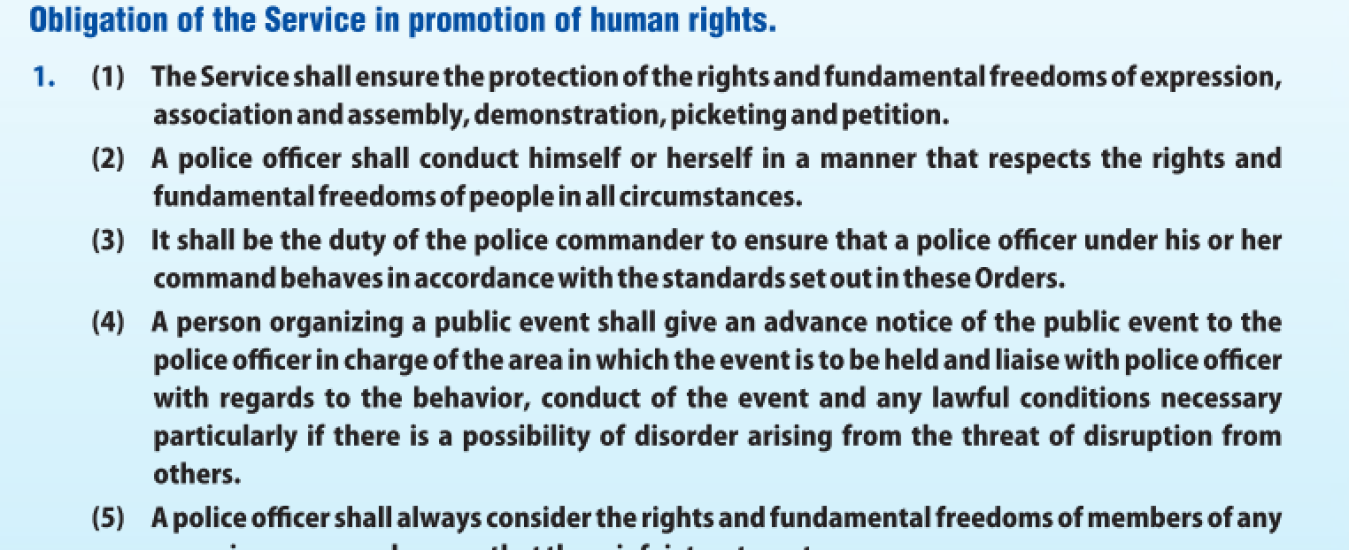

One of the interventions undertaken by IMLU and other non-state actors was undertaking police training on public order management and human rights. This was from the realization that training on public order control is an important part of police culture, yet a majority of the officers are not well-trained to deal with members of the public. The Kenyan Constitution and international human rights law require that police officer are properly trained in the lawful use of force and non-discrimination to prevent human rights abuses. Further, according to the National Accord Agreement, police officers should be retrained to the highest possible standards of ethics and integrity to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms and dignity of Kenyan citizens. For the police reform process to move forward, there should be strict adherence to the constitution, which requires “police to be professional, competent and accountable, respecting human rights and fundamental freedoms at all times”. Further, there is a need for increased political will and less interference in the police reform process.

The trainings were able to increase the officers’ understanding of their obligation in promoting human rights standards while managing the public, deterring the usage of excessive force by the officers when managing crowds. This was not only able to enhance professionalism in the management of public order but also developed their capacities in undertaking their mandate and ensuring respect for human rights, the constitution and rule of law during the electioneering period.

Having said this, the police need to work on the public perception that there are people who do not understand their role during riots and use excessive force out of anger. The police are also seen as intimidating, violent, government-oriented, inhuman, ruthless and unreasonable with no respect for the rule of law. Anger control can act as a buffer in situations of impulsive decision-making especially when such anger is induced during public order control.